Why an Inflation Spiral is Not My Central Scenario, Part 1: The Jargon

Genevieve Signoret

(Hay una versión traducida al español aquí.)

In a recent article published in La Carpeta Negra titled Easy Money, I wrote that I saw the risk of a global out-of-control inflationary spiral as minuscule. Here I start a short series to explain why. But, to do so, I need to use some jargon. So, this first article in the series is to give you the jargon.

Inflation is a generalized rise in prices, it is not a spike in one particular item or category. When just one or a group of items become suddenly much more costly while the prices of others fall, stagnate, or rise slowly, we’re observing not inflation but rather a change in relative prices.

For example, suppose a worldwide crude oil shortage causes U.S. gasoline prices alone to spike. Then we say that the price of gasoline relative to those of other goods has risen. Or, suppose bad weather hurts corn crops in the United States so that in Mexico the price of tortillas but only tortillas explodes. Then we say that the relative price of corn has gone up.

By the way, what I just described is what central bankers call a supply shock: a piece of bad luck that renders the supply of something all at once scarce and therefore expensive.

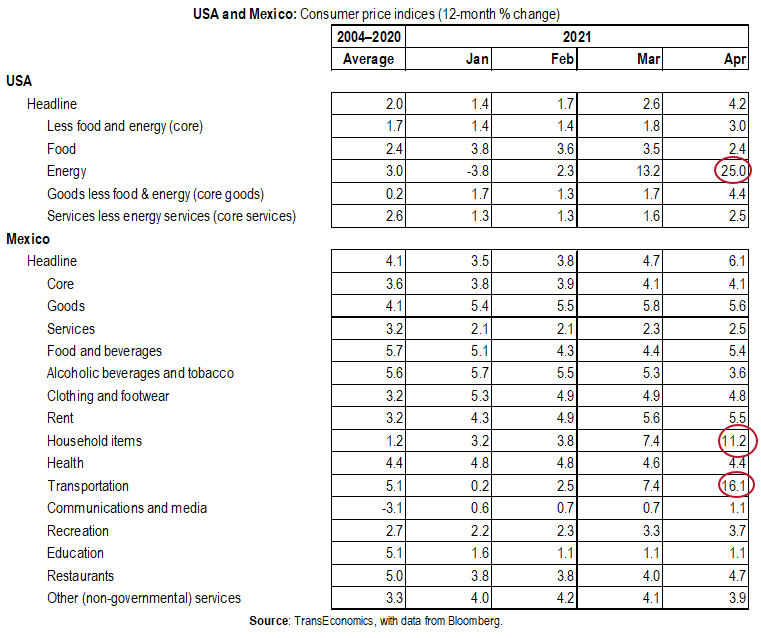

Changes in relative prices do not constitute a generalized rise in prices, hence, according to the definition stated above, they do not constitute inflation. In the table below showing inflation by categories for the United States and Mexico, we can see that only in certain categories—fuel in the United States and household goods and transportation in Mexico—have prices blown up. Hence, in both countries, so far, we are seeing not a burst of inflation as defined above but rather changes in relative prices.

With prices spiking only in certain categories, what we’re seeing is a change in relative prices

While changes in relative prices are not inflation, they can look like inflation. To see why, recall that the consumer price index (CPI) tracks a weighted average price of a representative group of final goods and services. Each item selected for the index is assigned a weight. If the sole item skyrocketing in price happens to have a large weight in CPI, then, even if the prices of everything else are moving quite slowly, that sole price spike can drive up the index so fast that it gives the illusion of inflation.

Because of that illusion, sharp changes in relative prices pose two risks. First, if the changes are strong and persistent enough, true inflation may take off. Second, if central banks are so fearful of risk number one that they tighten their policy stance prematurely, a recession may ensue.

Risk number one, that a mere change in relative prices will lead to true inflation, lies in people’s inflation expectations. The illusion of inflation, if strong and persistent, can cause people to start to anticipate inflation, setting off an upward spiral in wages and prices. Central bankers call this phenomenon the un-anchoring of inflation expectations, or second-order effect (of the original supply shock). One of their chief missions in life is to keep it from happening. Which explains risk number two.

Risk number two is that central bankers will be so nervous about the possible un-anchoring of inflation expectations that they will try to preempt risk number one, tightening money too soon. This can lead to a recession.

Just now I put the term tighten money in italics, because that phrase is jargon too. I could also have written tighten the monetary policy stance or taken a restrictive policy stance.

Currently in Mexico and the United States, monetary policy is loose, meaning that central bankers have taken measure to ensure that their customers, lenders, themselves have ample supplies of cheap credit. Commercial banks hold reserve accounts at central banks. Central banks create reserves (one component of base money) by crediting those accounts, either as loans extended to commercial banks or as payment for the purchase of financial assets.

Note that, in the paragraph above, I said nothing about the demand for credit; I spoke only of its supply. I focus on supply, because central banks have less influence over the demand for loans than they do over their supply. Plentiful demand and supply both are what drive up actual bank lending and the resulting propagation of bank deposits that blow up a small monetary base into large monetary aggregates (the money supply). A surge in both the demand for loans and their supply are needed for prices across the board to inflate.

In my view, the reason extraordinarily loose monetary stances taken by developed market central banks during the Great Recession of 2008—2009 did not set off inflationary spirals or even accelerate inflation rates up to central-bank targets was a lack of demand for credit.

Which leads to the question, why has demand for credit in developed markets been so weak? Macroeconomists offer competing theories that someday I may review here. For now, suffice it to say, it’s a mystery.

In my next segment, I’ll put all this jargon to use to explain why I see the risk of a global surge in true inflation (versus changes in relative prices) is miniscule.