Why an Inflation Spiral is Not My Central Scenario, Part 2: Cyclical Reasons

Genevieve Signoret

(Hay una versión en español de este artículo aquí.)

Now that you’re all fluent in the jargon economists use when talking about inflation and monetary policy, I will be able to use that jargon freely to lay out three cyclical reasons why I see the risk of a global out-of-control inflationary spiral as minuscule.

First, true inflation is not surging—what we’re experiencing is a change in relative prices owing to supply shocks in the form of supply bottlenecks.

Second, despite the illusion of inflation, expectations remain well anchored.

Third, money supplies are not accelerating.

Cyclical reason number 1: true inflation is not surging

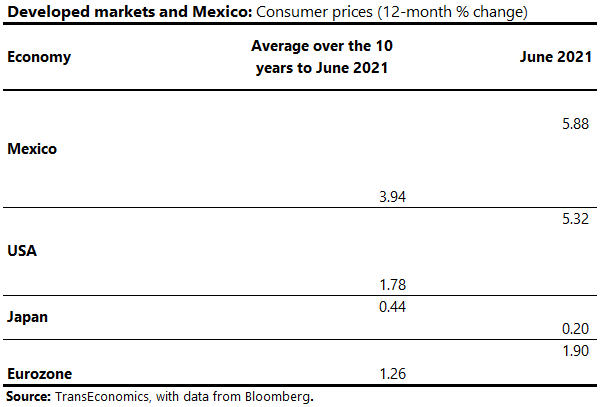

It does seem as if inflation were surging. After all, in the United States, the euro area, and Mexico, consumer price indices certainly are accelerating:

Consumer price indices outside of Japan are indeed accelerating

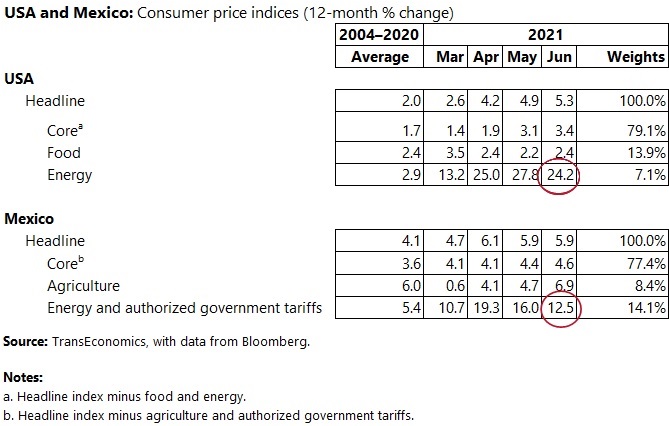

However, an update of the table I showed you last time should persuade you that what we’re observing is not true inflation—price increases are not generalized. Consumer price indices are accelerating on account of sharp spikes in the prices of isolated groups of items such as merchandise, fuel, and transportation, relative to the prices of other groups, such as services. This change in relative prices is giving the illusion of inflation.

However, because the price increases are not generalized, we’re observing not true inflation but rather sharp changes in relative prices

Cyclical reason number 2: medium-term inflation expectations remain anchored

Of course, there’s always the risk that a sustained illusion of inflation will cause inflation expectations to eventually become unanchored. It is precisely this risk that motivated the Bank of Mexico to hike rates on June 24:

Although the shocks that have affected inflation are expected to be of a transitory nature, given their variety, magnitude, and the extended time frame in which they have been affecting inflation, they may pose a risk to the price formation process. In this context, it was deemed necessary to strengthen the monetary policy stance in order to avoid adverse effects on inflation expectations, attain an orderly adjustment of relative prices, and enable the convergence of inflation to the 3% target.

So far, inflation expectations do not show signs of becoming unmoored.

We measure inflation expectations in three main ways: surveys of professional forecasters; surveys of consumers themselves; and the expectations implicit (we think) in bond prices. Let us now look at these one by one.

We start with medium-term outlooks for inflation held by professional forecasters for the United States, the euro area, and Mexico. Notice in the table that follows how stable these paths look:

For the medium term, professional forecasters see inflation rates stable

OK, so the expectations of professional forecasters have not become unanchored. But how about those of consumers themselves?

Because consumers tend to have little notion of where inflation rates lie, few data producers survey consumers directly as to their outlooks for inflation. The University of Michigan in the United States is an exception; through its Michigan Survey of Consumers, the school’s researchers do ask consumers to predict inflation. While we pay no heed to the levels of inflation expected (which respondents tend to overestimate), we do read fluctuations in these levels as evidence that expectations are shifting.

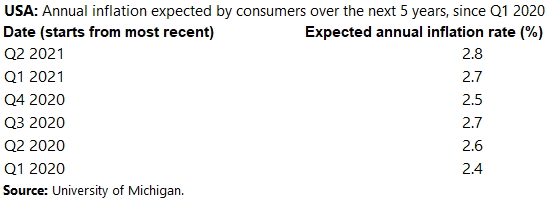

So, let’s look now at how consumers have forecast inflation for five years out per Michigan Survey results:

Views held by U.S. consumers on inflation five years out have scarcely budged

As you can see, at least in the United States, although we do observe an upward shift in what consumers see inflation rates reaching in the next five years, the observed shift is quite small (0.4 percentage point).

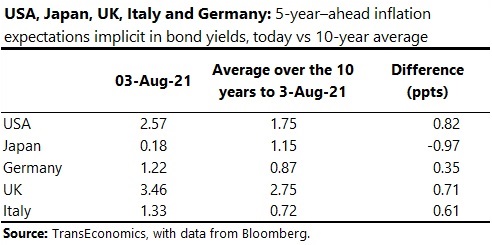

How about inflation expectations as revealed by bond yields? Economists glean them from the difference between the compensation (effective yield) demanded by nominal bond investors and that demanded by inflation-protected bond investors. Below, I show you these yields for the several developed economies. They have been risen from their 10-year average, but not by much.

Outside of Japan, inflation rates expected by bond market participants have crept up from their 10-year average by less than a single percentage point. In Japan, in fact, they have fallen.

Cyclical reason number 3: Monetary aggregates are decelerating

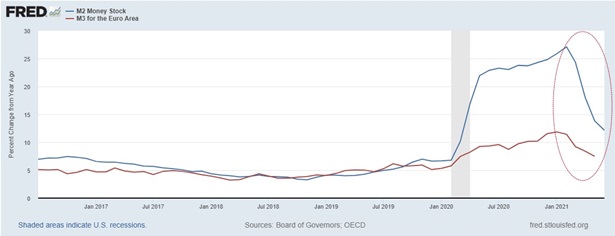

We turn now to broad monetary aggregates (money). If in fact inflation were about to explode, we would probably see exponential growth in broad monetary aggregates such as M2 in the United States or M3 in the euro area. But, as we can see in the following chart, instead what we see are monetary aggregates decelerating.

If global central banks were about to lose a grip on inflation, we’d see monetary aggregates accelerating, not slowing down as seen here

USA and euro area: Monetary aggregates, last five years (y/y % increase)

Source: FRED.

In summary, three cyclical factors support my view that global inflation is not on a runaway path:

- True inflation is not surging. What we’re seeing as the economy reopens are spiking relative prices caused by transitory supply shocks (bottlenecks).

- Inflation expectations are not shooting up.

- Monetary aggregates are not accelerating—instead, they are slowing down.

Cyclical arguments, moreover, tell only part of my story. Secular trends enter it too. To discover what I mean, stay tuned for part 3 in this three-part series.

Part 1: Why an Inflation Spiral is Not My Central Scenario: The Jargon