The Putin Effect (Stage 1): Macroeconomics

Alastair Winter

(Hay una versión en español de este artículo aquí.)

Macroeconomics: the Putin Effect is more like a catalyst

Mr Putin is said to crave international recognition for both himself and Russia and is certainly making waves in the global economy. However, it is probably best to see the invasion as a catalyst in developments already well underway, some pandemic-related and others going back even farther.

The most obvious immediate impact is on inflation, which now is set to rise even faster and persist for longer than seemed likely before the invasion. Still working their way through are supply and demand shocks caused by lockdowns and transport disruptions dating back to 2020. China is still notably struggling with the pandemic even as most other countries are just about coping—or at least think they are!

The Consumer Price Index (CPI) gets the most headlines, but it is the Producer Price Index (PPI) that is most exposed to the Putin Effect. It is driven by the prices of energy, food, and raw materials, for many of which both Russia and Ukraine are major global suppliers. To protect their profit margins, producers will always try to pass on their input costs so that consumers pick up the final tab.

Sure enough, PPI inflation rates are surging. The worst case is the Euro Area, where annual PPI inflation has reached 30%. But rates are surging elsewhere, too, with annual rates exceeding 10% and, in the UK, 19.2% in March. The surge in food prices will have the most severe humanitarian impact on poorer countries; the surge in energy costs will hurt the less well-off everywhere.

On a more mechanistic basis, energy and food price inflation sooner or later has a deflationary effect, as consumers in importing countries are forced to reduce their spending on other items while producers spend some of their only windfall earnings and do so chiefly in their home countries. Moreover, while Russia’s OPEC partners may be holding the line for now, they will surely be tempted by higher prices to increase output to take advantage today of assets that could later be ‘stranded’ by future global climate change measures.

Cash-strapped consumers are a recipe for future lower growth, just as the global economy is slowing down anyway and after having rebounded from the pandemic disruptions. Meanwhile, central banks have already begun tightening monetary conditions in response to pre-invasion inflation. The Fed in particular is turning up the heat.

There is, of course, a considerable ongoing debate as to how successful the central banks will be and how much collateral damage they may cause, but their actions will surely not be positive for growth over the next two years or more.

Unsurprisingly, global trade has taken an immediate hit from the invasion and related sanctions: not only exports from and imports to Russia and Ukraine but also from a knock-on effect in the EU. So far, US trade has been little affected and China trade hardly at all by the invasion. Yet the pandemic is causing major dislocations. A longer-term trend of re-shoring supply chains that picked up speed during the pandemic will likely accelerate further, even if the fighting in Ukraine stops soon.

All this is putting new pressure on governments to support growth just when most were hoping to cut back on pandemic spending and borrowing. Governments in most advanced economies are trying to help poorer families face rising energy and food prices while at the same time boost private and public sector investment.

Defence spending is now a new priority. Like his friend Mr Xi, Mr Putin is convinced that liberal democracies will fail but, contrary to his intentions, may well have provoked them into facing up to their major challenges: political disengagement, corporate responsibility, social inequality, and climate change. He may find consolation in sparking a global recession, although even that consequence of his invasion of Ukraine may turn out not to be severe or even ensue.

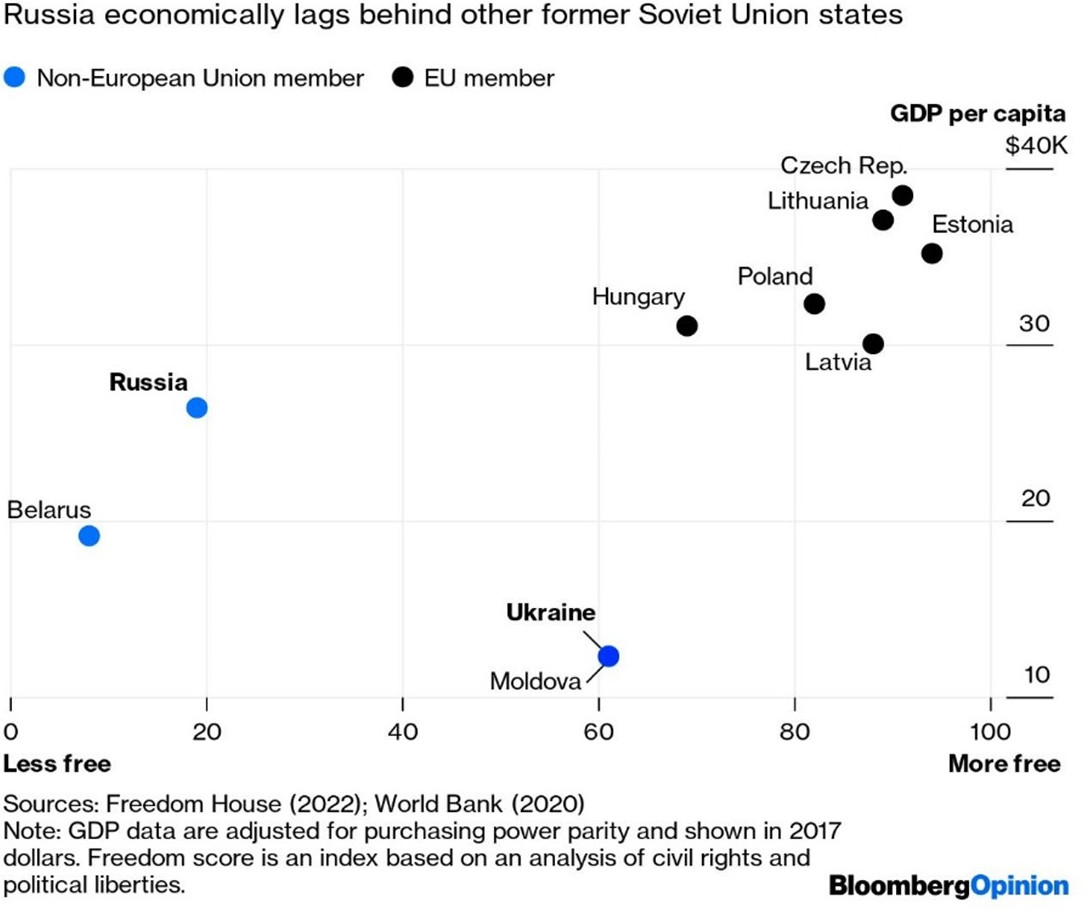

Figure 3: Unhappy comparisons in unhappy times

Meanwhile, despite all the indignant protests about the billions of euros’ being paid for oil, gas and coal, the Russian economy is heading for the rocks. Revenues from exporting fossil fuel may still be funding the war effort for now but customers will stop buying eventually, whether for political, financial, environmental reasons, or all three. It is only a matter of time before the EU turns off the taps, and Nordstream2 will never be activated. In fact, there is a chance that Mr Putin will cut off supplies in a desperately defiant bid to halt the EU’s active support for Ukraine.

International companies and professional organisations have been remarkably willing to bear substantial losses from ceasing to operate and trade in Russia (and Belarus) and are unlikely to return for many years, if ever. Sanctions can be scattergun in their effectiveness, but the focus this time on SWIFT make them potentially devastating for those who seek to infringe them. This fact seems to be deterring even companies based in pro-Russian countries such as China, leading to job losses and pay cuts for their Russian employees and business partners.

Technology workers are something of an elite in Russia, and tens of thousands of them (reportedly up to 300,000) have fled in recent weeks. Russia’s manufacturing base has suffered from lack of investment in new industries and become dependent on imports for high-tech components and finished products, including for armaments.

The central bank will, of course, be able to print roubles, and foreign buyers will need them to pay for the oil and gas, but hyperinflation is looming large along with recession. Wars are notoriously expensive, and Russia could run out of both money and weapons before the end of the year. Perhaps blinded by his nostalgia for the former Soviet Union, Mr Putin has repeated the mistake of spending too much on the armed forces and overseas adventures, while not doing enough to encourage business investment and consumption.

In short, the Russian economy is wrecked. This is what happens when a despotic leader is surrounded by corrupt sybaritic acolytes.