Central banks risk pushing economies into recession

Genevieve Signoret

(Hay una versión en español de este artículo aquí.)

The following is an excerpt from Quarterly Outlook. Click here to read the full report.

While it is true that European Central Bank (ECB) officials have been more cautious than Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) members, they do now talk of enacting two rate hikes in quarter three. Given weak demand in the euro area and unknowns surrounding a possible impending fuel embargos on Russia, we see this as a mistake.

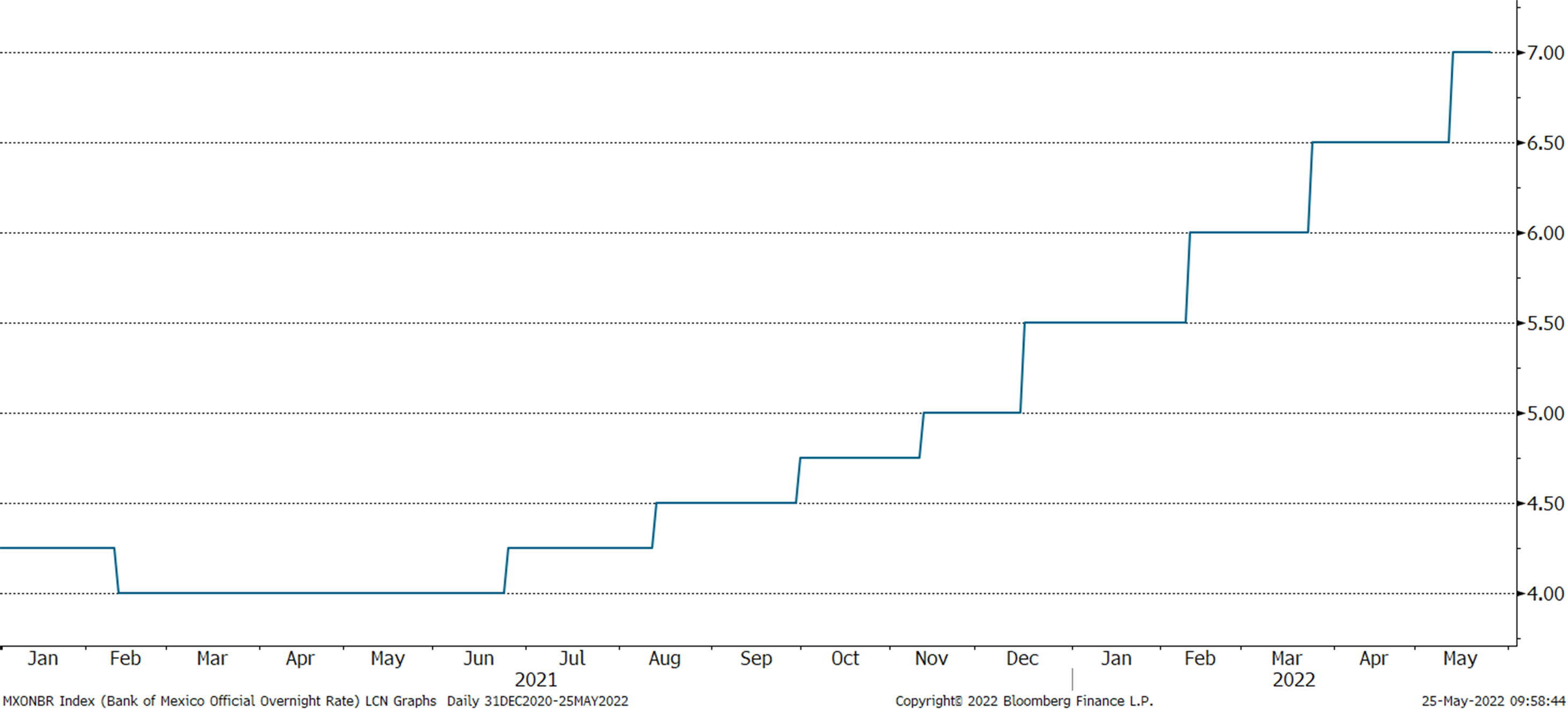

Banxico not only has already hiked rates eight times by a total of 300 basis points since last June 2021 but also has practically promised to deliver a 75–basis-point hike next month. Given weak aggregate demand in Mexico and stable long-term inflation expectations, we find Banxico’s aggressive posture puzzling.

Frustrated by persistently high inflation in our view explained by global supply shocks, Banxico is ramping up its tightening by hinting that in June it will hike rates by 75bps. With demand weak and long-term inflation expectations stable, we find this puzzling.

Mexico: Monetary policy rate, since January 2021 (% rate per annum)

Source: Bloomberg, TransEconomics.

Research assistance by Estefanía Villeda. Editing by Andrés Aranda.

I am grateful to have the opportunity to exchange views with the team at TransEconomics Research. Here, I would like to comment on the Quarterly Outlook published on 26th May. Let me say up front that I agree with the six key beliefs that underpin the analysis but with one caveat which, for reasons that will become clear, is actually rather important. I also broadly agree with the likelihood of a ‘Soft Landing’ scenario although with greater conviction and not for all the same reasons as set out in the Outlook.

My caveat concerns monetary policy, which it is undoubtedly true ‘can spark or stifle demand’. However, I would argue that central banks have effectively lost the ability to ‘spark demand’ through their regime over many years of ultra-low interest rates and large-scale asset purchases. Ever since Fed Chair Jerome Powell spoke out last August it has become clear that he and his colleagues at the Fed and other central banks are determined to regain that ability. They really do want, as well as intend, to hike interest rates, irrespective of the state of the global and national economies and irrespective of any consequent market reaction. The justification for risking short-term adverse market reaction (as, indeed, we are currently experiencing) is that the central banks would once again have the tool of monetary stimulus in the event of a major downturn. Nevertheless, it all seems to have come as a shock to many investors who had long feasted on cheap money and slept well at night in the comfort of the implicit Greenspan and explicit Bernanke ‘puts’ should anything go wrong. More prescient investors had already detected in Janet Yellen an increasing ambition to phase out the loose policies of her predecessors but were then reassured by the appointment of Wall Street insider Powell as her successor.

The disillusionment with Mr Powell that has been building since August has led to a widespread obsession that the Fed will drive the US economy into recession. One group of critics fear that the Fed is tightening too much too soon and as a result they are starting to buy bonds again while shunning growth equities. Other critics fear the Fed is not tackling inflation with sufficient vigour and will have to take more drastic steps down the track and as result they are sellers of both US equities and bonds and buyers of commodities (all of which is, in turn, undermining the dollar’s resurgence as a safe haven). For both groups, the main concern is recession rather than inflation itself and, especially in the case of the US, the economic data is conflicting: with employment, earnings, retail sales and industrial production going strong while both business and consumer confidence surveys are getting softer.

The data may be making the Fed’s job even more difficult but it is hard to be sympathetic when it has been so hubristic in the past over its ability to control the economy. Over the past decades I have seen theories rise and fall and am more convinced than ever that most economies, both advanced and developing, are too complex to be controlled by anyone. Accordingly, in sharing with TransEconomics the expectation of a soft landing (or ‘softish to use Mr Powell’s description) for the US economy, I do not believe that outcome will all be due to a masterful Fed. I do agree with TransEconomics that inflation will fall back quite sharply and recession avoided, albeit that the wider global economy faces an extended period of low growth. However, I do not believe the Fed will stop hiking rates in 2022 and will carry on until they reach a range of 2.5-3.0%.

I defer to TransEconomics in their assessment of Banxico policy decisions and accept that the Mexico will join many other developing economies in experiencing an extended period of low growth and even a shallow recession. I also agree that the EU economy is heading into recession but more because of the squeeze on demand from a combination of supply shocks and soaring food and energy prices rather than aggressive tightening by the European Central Bank. I do expect that an embargo on Russian oil will be maintained and that Russia will retaliate. As Brexit continues to bite and the Johnson administration runs out of both ideas and excuses, the UK economy faces a grim period of inflation followed by recession. I am more pessimistic than TransEconomics on the date for the start a new bull market in US equities and even more so in other advanced economies but there should be opportunities in EMs, including China (despite its slowdown) and the larger ASEAN economies. In contrast, the outlook for fixed interest assets is more benign, judging by the willingness to buy 10-year US Treasuries whenever the yields approach 3%. One should always be wary of booms in commodities and food prices are now more likely to spike higher than oil and gas. The dollar has most recently seen some profit-taking after a strong run since Mr Powell spoke out last August but it remains the safe haven of choice, even if the bad news is coming from within the US.