Don’t shoot the piano player, Part 3: the next two years and beyond

Alastair Winter

(Hay una versión en español de este artículo aquí.)

This is Part 3 of a four-part series by Alastair Winter. Parts 1 and 2 are found here:

Don’t shoot the piano player, Part 1: central bankers under fire

Don’t shoot the piano player, Part 2: how did central bankers err?

Alastair Winter of course writes on his own views, not those of TransEconomics or Genevieve Signoret.

Year-on-year inflation indices everywhere will stay high well into 2023 but, because of the way they are calculated, they will fall—possibly quite sharply—as soon as the monthly increases slow.

The global economy is already in the midst of a multi-year slowdown with all the usual locomotive economies (US, China, Germany) failing to provide relief. Among major economies, only India, Indonesia, and Singapore are experiencing significant growth, while in several developed countries recessions loom.

Surging energy and food prices are threatening general inflation by driving up costs, growth by diverting consumer spending away from other items, and a wage-price spiral. While the pressure on food prices may ease in the coming months (at least in the US), the opposite is true of energy prices, as Russia seems prepared to risk losing its European market permanently to further its war aims. Meanwhile, Saudi Arabia—the other leader of the OPEC+ cartel and no friend of the West—has a different priority: maximize revenue for as long as there is demand for fossil fuels.

Higher interest rates will help dampen demand through their impact on consumption, business investment, and, eventually, government spending. The US economy is better placed than most advanced economies despite two consecutive quarters of negative GDP growth (a technical recession). It is largely self-sufficient, even in energy. And will be helped in several ways by the (somewhat misnamed) Inflation Reduction Act. In contrast, all of Continental Europe and the UK seem doomed for the next few years to slow growth or recession, energy shortages, hardship for the less well-off, and industrial and social unrest. Central banks will scarcely be able to help while inflation remains so far above their 2% target. Governments will have to intervene on an unprecedented scale.

Despite the outlook for central bank rates, institutional investors seem relatively comfortable that short-dated bonds yields will not fall much while the outlook for economic growth will constrain longer-date yields from rising much, resulting in an inverted or flat curve. Bearish bets by hedge funds and other leveraged investors are creating more volatility than usual, however. Still to be tested are outright sales by central banks of their vast holdings of government bonds, as opposed to a mere running off of assets as they mature.

Some investors appear to be looking beyond the hikes in official rates and the bad economic news. But any rally in advanced economy equity markets will likely be limited for a while yet. U.S. equities look both fragile and expensive after the July rally, but the current resurgence in the dollar is, for now at least, restricting flows into even the strongest developing economies. Domestic European and UK companies, especially, are exposed to the bleak macro outlook.

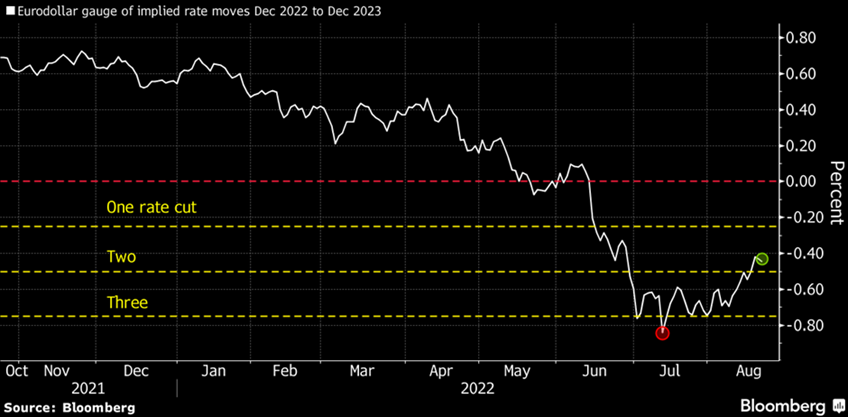

Figure 3 Fed rate cut(s) are coming in 2023 but later and smaller