Quantitative Tightening Continues … for Now

Genevieve Signoret & Delia Paredes

(Hay una versión en español de este artículo aquí.)

Sheepish Warning

Before jumping into this post, we sheepishly warn you that its content is more technical than we strive for in Timón Económico. It refers to something we need to but have yet to post a primer on—namely, the Fed rate floor system; how it contrasts with the corridor system that was in place before the Great Recession; and why, under today’s floor system, the Fed needs to hold astronomical amounts of “reserves” (commercial bank deposits).

We promise to write and post that primer in coming months! Meanwhile, to any economists among you itching to dig into the topic, we recommend this short piece from Mercatus Center as a starting point.

Today’s Timón post refers also to “the long-term debt securities” the Fed holds in its investment portfolio and the term “government agencies”. The Fed is a lender not only to the Treasury but also to various government-sponsored agencies. Thankfully, we need not publish a primer on agency bonds. Good old Investopedia has already written a perfect one.

Finally, we refer below to the Fed’s “management of its balance sheet”. This phrase is standard lingo, but it’s weird, because it refers simply to the one side of the Fed’s balance sheet, the asset side, and specifically to its bond holds.

QT Will Taper, Then End—Probably This Year

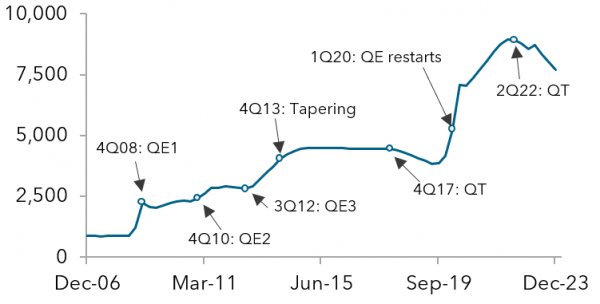

The Federal Reserve is persisting in its Quantitative Tightening (QT) program, whereby it allows the long-term debt securities it holds in its investment portfolio to mature without replacement.

QT continues (for now)

USA: Federal Reserve total assets, US$B

Source: Bloomberg.

At some point, probably in the next six months and, for reasons related less to the Fed’s monetary policy stance than to banking system liquidity requirements under the floor system the Fed now operates under, the Fed will need to end QT. It will not do so abruptly but rather it will taper QT by resuming its prior practice of reinvesting a gradually increasing proportion of the proceeds of cash flows from maturing Treasury and government agency bonds.

Yields paid by long-term bonds respond to the interplay of bond supply and bond demand. More supply or less demand drive rates up; lower supply or strong demand drives them down. The tapering and eventual end to QT will raise the Fed’s demand for Treasury securities because it will entail reinvesting at first some and eventually again all the cash flow the Fed enjoys as bonds mature.

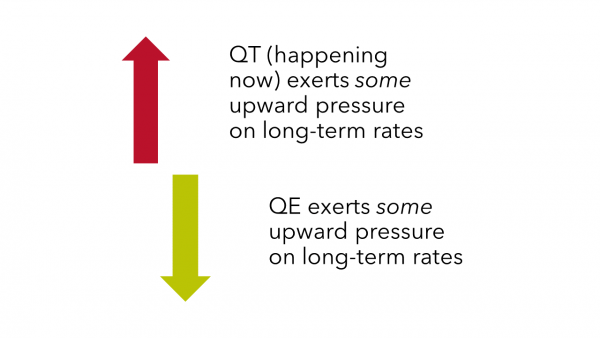

Financial economists disagree on how strong the up-or-down pressure on rates the Fed actually exerts through the management of its balance sheet. We’re agnostic on this point. Rather than take a stance as to the strength of the influence, we simply adopt the working hypothesis that, all else being equal, the direction of influence that anticipated and actual QT exerts on rates is upward, and that that of a tapering off of and eventual end to QT is downward.

Our working hypothesis is that QT and QE do influence long-term rates to some degree, as shown here. As to the strength of that influence, however, we’re agnostic.

Assumed effect of anticipated and actual Fed balance-sheet management on long-term rates

Source: TransEconomics.

Corrected on 6 March 2024.